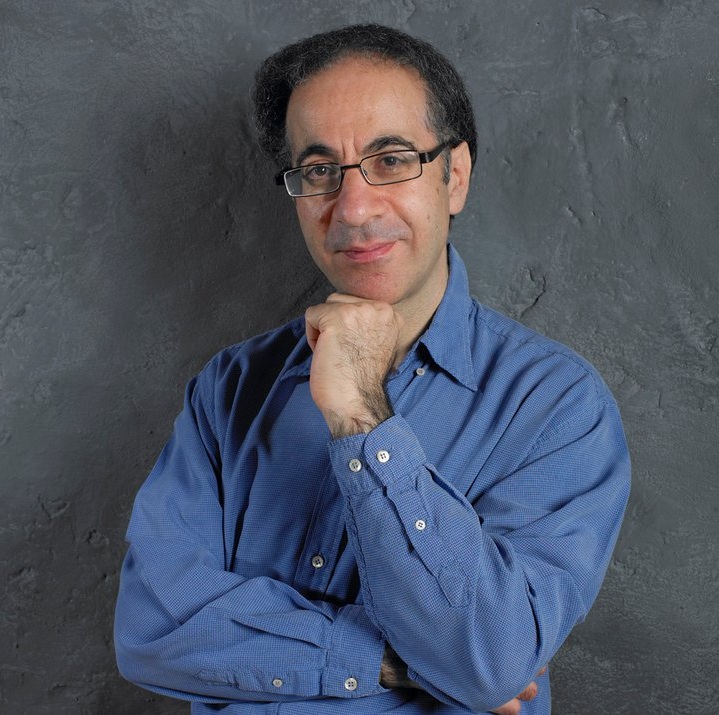

Paul Harris considers... playing scales (part 2)...

When I used to run a music department there was one particular teacher who simply wouldn’t teach scales. She disliked them so much that she absolutely refused to teach them. I ended up having to teach her pupils their scales and it wasn’t even my instrument. And to make matters worse, the pupils knew their teacher’s view. So I began with a massive disadvantage! Even those who didn’t really know what scales were, thought of them as somehow evil. I certainly had my work cut out to find ways of making them palatable.

I’m a great believer in the process being more important than the outcome. In this case the outcome was learning some scales (for some, learning scales for an exam). The process was to be concerned with introducing the idea of scales and scale learning and that process needed to be imaginative, relevant and fun. So I began to develop a method where actually playing the scale would come at the end of what I hoped would be an interesting and, yes, an agreeable journey.

So we began with thinking about what a scale is. It’s a collection of notes that form the building materials of a piece of music. So which scale to begin with? Simple – our own scales. Each pupil was sent home to create their own scale. They could choose any five notes (which included flats and sharps as long as they could play them). Some wrote their scales down, other remembered them. We enjoyed hearing each pupil’s collections of notes which were named after themselves – Robert’s Scale, Sally’s Scale... We hadn’t necessarily put the notes into alphabetical order yet. Their next assignment was to make up a short piece based on the notes of their scale. That seemed to go down well too. Again, we enjoyed hearing the interesting pieces based on each pupil’s made-up scale. Then they wrote their scales down and went home to make up another short piece, but this time based on a friend’s scale. Once more, the results were most enjoyable.

They had, straight away, taken on the idea that scales were okay – even fun – and that they formed the basis of pieces. Next we had a look at someone else’s scale, and the obvious choice was a pentatonic scale – just like theirs. So we learnt to play the pentatonic scale and some little pieces I found based on it. We took some of the other ingredients out of the pieces (rhythms, dynamic and articulation markings) and applied these to the scale. It seemed a sensible thing to do to make practising it more interesting. And they agreed.

So now to make the leap to the scales of the pieces they were learning. We looked at the pieces carefully, decided on the scale used and spotted patterns in the music. Were there any technical issues to consider? If there were we created some short exercises to help overcome these. Then we improvised in the key: call and response sort of activities, always being careful only to use notes of the scale. We added other ingredients. Then I found some short studies in the key based on the scale patterns. Next we attempted to play, by ear and in the key, phrases from pieces they knew – the first phrase of Jingle Bells, the opening phrase from EastEnders. Eventually we decided that all technical problems had been overcome and the notes were well known. It was time to perform the scale. As a preliminary, the note names were said out loud – up and down. Then one or two ingredients were added from the piece – a dynamic and a character for example. Finally we had reached our outcome, a performance of the scale, played with relevance and good will. The process had been fun and imaginative. The outcome – playing the scale accurately, with character and with some real satisfaction – had been achieved.

I tell this story because there are many ways to teach and learn scales. If we teach them dryly and only because they have to be learnt and played at some distant event (an exam for example) there is little joy to be had. If it’s felt there is not enough time to devote to such teaching, then perhaps it’s necessary to decide why we’re in such a hurry. Scales are important; they are the building blocks of both pieces and technique and can be quite pleasant, to teach and to learn, if approached with a little imagination.