In the Summer of 2000 I had the great pleasure of meeting James Gillespie, editor of The Clarinet Journal, during the International Clarinet Association (ICA) convention in Oklahoma. James asked me if I would like to contribute a regular column – an invitation that I found both humbling and daunting! The following ‘Letter from the UK’ was first published in March 2009 in The Clarinet Journal, the official publication of the ICA.

So much of the clarinet repertoire has been born of the collaboration between performer and composer: Stadler and Mozart, Baermann and Weber, Muhlfeld and Brahms are of course the most renowned. But there is a much less well-known relationship that blossomed during the second half of the twentieth century and produced an important collection of clarinet works.

To locate one half of this partnership we need to travel to Scotland, and find a composer whose considerable body of clarinet music richly deserves rediscovery. The composer in question is Iain Ellis Hamilton (1922–2000). And the clarinettist was fellow student and close friend, John Davies. The two young musicians met at the Royal Academy of Music in 1947. At first they formed a clarinet/piano duo, working their way through most of the repertoire. But Iain was there primarily as a composer (a student of William Alwyn, who himself wrote a very effective clarinet sonata) and soon began working on a series of important works for John. These works are now almost completely (but certainly unjustly) forgotten.

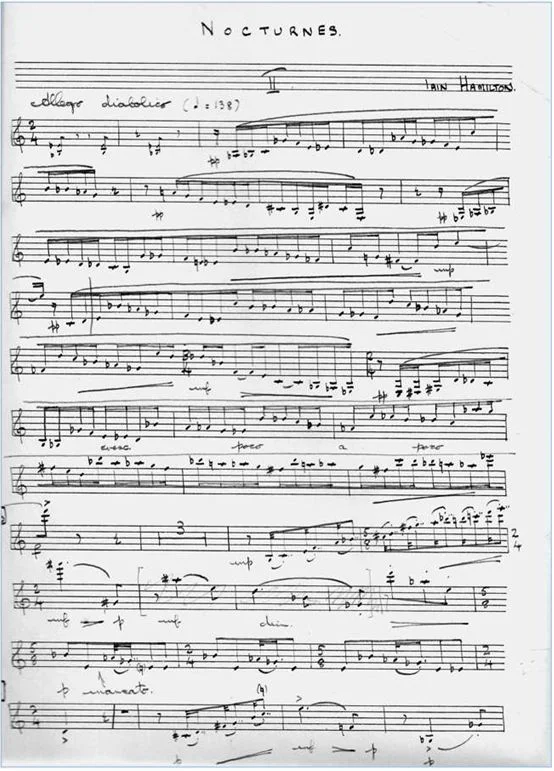

John Davies remembers, ‘He was a tremendously serious and energetic man; worked 48 hours a day. I don’t think he ever went to bed – he couldn’t stop!’ The violinist Nona Liddell found him ‘a little nervy, but very warm-hearted – a true Scot!’ He and John gave recitals all over Europe: Brahms, Ireland, Hindemith, Bax and Weber’s Silvana Variations were among their favourites. I now have the (well-annotated) copies they used in my own library and they offer many insights. A year after their meeting, Iain composed his first work for John; a clarinet quintet. John gave the first performance with the Liddell Quartet (led by Nona Liddell. ‘And a jolly good work too!’ she told me enthusiastically at a recent meeting.). John later broadcast it on BBC radio with the Aeolian Quartet in 1950. Though very interested in the latest serial composers, Iain’s own style at this time was more an amalgam of Bartók, Berg, Hindemith and Stravinsky, giving his music both rhythmic drive and a vivid harmonic colour. Next came his Three Nocturnes for clarinet and piano – perhaps his best known work. John gave the first performance on BBC Scottish radio in 1950 with Iain accompanying. The first London performance was given by Jack Thurston in 1951. They challenge a little, but are enormously worthy of study and performance: atmospheric and audience friendly.

In fact John and Iain regularly gave recitals in Scotland, at the central library in Edinburgh. These concerts were organised by Tertia Liebenthal, who also happened to be a passionate cat lover. Not only did Tertia arrange the concerts, she also reviewed them for The Scotsman, under the pseudonym Zara Boyd (her cat’s name). One evening however, the concert series came to a sudden and abrupt end. She and Iain were in a taxi making for the venue – they were late and John was already waiting uneasily. On the way, Tertia spotted a cat in distress by the roadside. ‘Stop the taxi!’ she demanded, the cat’s rescue now taking unquestionable priority over the concert. Iain was unhappy about this further delay and in his anxiety maliciously announced to the cat lover that ‘John had eaten cats you know, when he was a prisoner of war.’ It was to be their last engagement at the Edinburgh library...

Later in 1951, back in London with cats now forgotten, Iain composed his virtuosic Clarinet Concerto which won the prestigious Royal Philharmonic Prize. Though written for, and dedicated to John, it was Thurston who gave the first performance with the RPO. Jack Brymer gave the first broadcast performance. A Divertimento for clarinet and piano came next in 1953, followed by the Clarinet Sonata, once again dedicated to John, who gave the first performance in Paris in 1954. In 1955 came both a Serenata for clarinet and violin, written for John and Frederick Grinke (displaying a move to a more severe serial style) and the Three Carols for six clarinets, which Iain wrote for a group of John’s students at the Academy: fascinating, imaginative and useful arrangements (published by Queen’s Temple Publications).

In 1961, Iain moved to America where he became Mary Duke Biddle Professor of Music at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He was also was composer-in-residence at the Berkshire Music Centre at Tanglewood, Massachusetts (in the summer of 1962). He was to remain in the U.S. for twenty years, writing many wind chamber works among his large output.

There was a long break before Iain turned once again to the clarinet. And it was to be for the last time. In 1974 his opera The Catiline Conspiracy was receiving its first run at the Scottish Opera and, in the pit, playing principal clarinet, was the young Janet Hilton. She was enjoying the work so much that she personally commissioned Iain to write a new work. He wrote her his second quintet, evocatively entitled Sea Music. Janet gave the first performance at the Bath Festival with the Lindsay Quartet. Like all Iain’s clarinet music, the work provides a certain challenge for the performer, but it is more lyrical and rhapsodic, more tonal than some of his earlier works. Janet remembers that the composer took a lot of interest in the rehearsals and seemed particularly pleased with the performance. The London Observer called it ‘an attractive score, full of brilliance and light’. Most of these works are available from Theodore Presser Company.

Looking through the Iain Hamilton manuscripts in preparing this article, I found something amongst them that sent a real shiver of excitement tingling down my spine! I’m working on the Mozart concerto for a performance soon and had been giving quite a bit of thought to the whole business of cadenzas. What I found, most providentially, was a single sheet of manuscript paper on which Iain had composed three intriguing cadenzas for the Mozart; two for the first movement and a beautiful third for the slow movement. I now know exactly what I shall be doing for cadenzas!

The first manuscript page of the second Nocturne. Those who know the work will notice a significant adjustment of metronome mark and various other interesting alterations (including the deletion of three bars).