Interviews

In Focus: Paul Harris (AMEB)

July 2023

What first sparked the beginning of your musical interest?

It's a slightly complicated question.

We all arrive at our interests from slightly different angles - maybe even multiple angles. And in my case, it was undoubtedly multiple angles. A specific and most important event was when we unexpectedly inherited a piano when I was about six. It was a small, rather rickety old grand piano, and we had quite a small house, so the piano ended up in my bedroom. I had no room and had to navigate around the piano, which I loved.

I'd make stuff up on the piano, you know, I didn't have piano lessons, but I enjoyed playing this and that. I was absolutely appalled one afternoon when I returned from school to find the piano in the garden being chopped up for firewood. I was so upset that my parents had to buy me a small electric piano to take its place. They didn't realise how attached I was to this piano. And by this time, I had started clarinet lessons at school and had the most wonderful clarinet teacher, John Davies, who was my mentor and inspiration (until he died). He was the most amazingly wise and generous personality who influenced me enormously. I've always understood that teachers are immensely important in one's life. And luckily, having had a really good teacher, I truly understand what an enormous difference they can make.

What were the teaching approaches that stuck with you at that age?

The concept is that teaching is an act of sharing and an act of generosity embedded in kindness. A very shallow concept of the whole teaching process is, “I’m the teacher because I know more than you do, and therefore I teach you what I know”. Education is much more than transmitting ideas, skills, or information. My teacher (John Davies) had a wonderful concept of sharing.

Did that experience contrast with your formal education?

I was lucky to attend what I'd consider a school slightly ahead of its time. I had numerous teachers who shared information rather than transmitting it. There were some teachers who were awful, too. I was lucky to see both sides of this coin and understand what constituted exemplary, thoughtful, and inspirational teaching… and also what was of lower quality.

You studied clarinet at the Royal Academy of Music and then education at London University. Was education always a part of what you planned to do at some point, or did that evolve as you studied music?

My clarinet teacher at school, John Davies, was also the Senior Clarinet Professor at the Royal Academy of Music, so I continued my lessons with him.

One of John's great qualities as a teacher and a mentor was instinctively knowing which direction to guide his students. Many of John's pupils are now world-class players and music coaches in orchestras in the United Kingdom and further afield. And others do slightly different things. For example, one of his pupils is now the Principal of the Royal Northern College of Music. And another of his pupils is the Director of the Nash Ensemble, one of the world's leading chamber music ensembles. John seemed to have an instinct about my interest in teaching which he nurtured from very early on.

Through my Royal Academy years, he helped me to move in that direction. And then, when I finished the Academy, he said, "I think you should do a year at the London University Institute of Education." I wasn't excited about doing it, but I did it, and certainly enjoy it more in retrospect than I did when I was doing it!

But he was absolutely right! Studying education gave me that basis in the philosophy and science, as it were, of teaching. And I learned many important things, as John knew I would. My tutor at London University was Keith Swanwick; you'll probably know his books like Teaching Music Musically. He was the head of the Department of the Institute at the time and a great mover and shaker in the world of music education. I was lucky to have such an interesting tutor.

From the title of his book, you tell Keith Swanwick's got a great, sincere wit and humour.

Absolutely. He certainly did and still does.

You've researched Specialist Music Education for Highly Talented Students, were there patterns in teaching, learning, or practising that helped define struggling or talented students?

The research occurred because I taught this extraordinary young lad called Julian Bliss (who has become one of the world's leading clarinet players). I started teaching Julian when he was six, and he was remarkable even then, and I was very interested in this kind of mindset.

But the interesting answer to your question is I don't believe in the word or the concept of talent. Some people have an extraordinary instinct and a way of rapidly soaking up copious information.

We need to be careful not to think there are good pupils and less good pupils. We have faster and slower pupils, and slower pupils are not bad pupils. They're just slower pupils.

What I've been gathering more and more as I develop my thinking is if someone wants to learn and we teach them in a particular way, nothing stops them from going as far as they want. It is the teacher's gift rather than the pupil's talent. I hate the idea of good and bad pupils in a teacher's mind.

When did the idea of Simultaneous Learning galvanise for you? From this discussion, Simultaneous Learning is something that you've probably been doing for a while and needed a way to explain the process so other people could learn from your experience.

That's precisely the way to describe it.

From the beginning, my teaching style went in a similar direction to John’s style of teaching, who inspired and taught me in this kind of way. I wanted to develop an approach that facilitated good experiences and moved in a positive direction all the time. Because that's how I wanted it to be taught, the Simultaneous Learning approach to teaching gradually became more evident in my mind until I sat down and thought, well, I need to write about this

It was relatively easy to put it together as an approach. I call it an approach rather than a method. If you are a teacher of any other method like Suzuki or Kodaly, you can still apply the Simultaneous Learning approach. I'm not here to tell anyone what you should teach. I'm interested in how you teach it. So, if you want to teach through other methods, that's fine. The Simultaneous Learning approach emphasises joy, and in the education sector and globally in many industries, there have been more discussions and focus on mental health and burnout.

What was the feedback you've received from teachers about this approach, and how has it impacted their students?

I get feedback regularly.

Not necessarily every day, but very regularly, people write to me. Many people say it's changed their life. The principles of Simultaneous Learning make pupils the most important part of the process. Because they understand the process, progress is constantly made and perceived, which is ultimately very motivating.

When you get there in your teaching, your pupils are happy because they know what they're doing and have control of what they're doing. So, if you're in control and create pupils who are themselves in control, you have happy and content pupils. They're content because they control their actions and understand their purpose. They're moving forward in a way that they entirely understand.

You've published over six hundred books - an amazing feat for anybody. What was the impetus to share your knowledge?

It began when I started teaching the clarinet, and obviously had to use the available teachers' books. They lacked imagination and did not move at an appropriate speed. So, I started writing my own clarinet tutor, which I just printed out on a photocopying machine and gave to pupils. And then someone said, "Why don't you try to get that published?"

So, I did—my very first publication, The Cambridge Clarinet Tutor, because Cambridge University Press published it. I worked at a Cambridge school then, and someone recommended I go to Cambridge University Press for publication. That's how it started, and I'm now addicted to it! I write all the time. But I hope that I write stuff that is useful to people and try to break down learning into appropriate incremental steps. Most of the books I write are to provide pupils and teachers with interesting material to make learning fun and take them on a clear and understandable journey.

I Can Compose! - Interview with Paul Harris (October 10th 2022)

By Rachel Shapey

Tell us a bit about your musical journey…

It all began with a wonderful teacher – as it should! John Davies, who went on to teach me at the Royal Academy of Music, was also my first clarinet teacher at school. He was one of those truly inspirational teachers. During one lesson he said to me, as I was playing the next piece in my tutor book which happened to be the National Anthem, “there really ought to be a piece called ‘God Save Mr Davies’… I wonder who might write that?” Of course, I went home and wrote it – a little piece for clarinet and my first ever composition. I was about 10. I became hooked on writing pieces and by the time I entered the RAM had quite a drawer-full.

As well as studying the clarinet and piano, I had composition lessons with Timothy Baxter – a delightful man and a pupil himself of the South African composer Priaulx Rainier and Aaron Copland. My first publication was in fact a Clarinet Tutor – I was rather dismayed by the teaching material I found available when I began teaching and thought I could do better! I was amazed when Cambridge University Press actually decided to publish it. And since then, I’ve never stopped composing. Mostly for particular people or events or occasions. And a lot of what is curiously called ‘educational music’ – not a term I especially like. I prefer to think of it as seriously written music that is often used in education. I’ve also written a ballet, 7 or so concertos, a children’s opera and a fair amount of orchestral and chamber music. Below you can watch my Buckingham Concerto No 5 (for piano duet), a piece I am particularly proud of!

You have written over 600 publications within music education – what keeps you going, how do you stay motivated?

Happily, I just do! I hope, through my music, to bring a smile to someone’s face; to cheer them up; to make them think… to elicit some reaction. That potential reaction is what keeps me motivated. I’ve never felt the desire to write music just for the sake of it. My motivation is ultimately to help others find the huge pleasure that music can bring and which I have always enjoyed – and I hope to continue to do so for a long time still to come!

Your latest book ‘Musical Doodles' is all about rediscovering a love for writing down music through musical doodling. Can you describe some of the activities included in the book?

Making up music is a very natural thing. Sometimes we whistle a tune when we’re feeling in a good mood, or hum to ourselves as we’re searching for something in the local supermarket. But over the years learning to make up music or compose, has become a complex undertaking. Composition books are often long and complicated and full of rules. Of course, if you wish to learn those rules that’s great. And as a result, you may be able to write some meaningful and sophisticated music. But it’s quite an intimidating and daunting journey that most probably won’t embark on. Many musicians I think would like to compose. So, in ‘Musical Doodles’ I have tried to create a journey that anyone can take. With just a little musical knowledge we can begin to write some music simply using what we already know. Without having to worry about rules we find we can actually start writing music. It’s really quite simple! And from little acorns…

Do students need to be able to read staff notation to get the most out of the book?

Some basic musical knowledge of notation – gained from playing an instrument for example, will certainly help. But if you don’t – you can still have a go!

You have composed countless (much-loved) pieces for students, from piano sight-reading collections to books for woodwind, brass, strings and voice. How do you start a composition – what is your process?

Thank you! It’s a very practical process really. When writing teaching pieces, I begin with a list of musical and technical ‘ingredients’ which become the building blocks of the piece – it’s then a case of putting them together in a way that will be both effective as a means of delivering whatever the teaching/learning outcome has to be, and also in a way that creates music that is attractive and enjoyable to play and to listen to.

Do you use any particular notation software programme?

I’m quite a fan of Finale – but I have Sibelius too. I almost always start at the piano though. As a child I used to improvise a lot, especially exploring harmonies. I remember discovering the secondary seventh – a sound I love and which you’ll find inhabiting much of my music. My father didn’t get improvising; ‘do some proper practice’ was something I got rather too used to hearing!

As a first-study clarinettist how do you approach composing for an instrument you don't play yourself?

I learned to play the piano, and the violin as well at school (I managed to get Grade 8 violin …merit!). So that gives me quite an insight into string instruments. When I recently wrote Improve Your Sight Reading! for Guitar a friend lent me one and I worked it all out on the instrument. Otherwise, I read about and take lots of advice from friends who play the instruments I write for but don’t play myself.

Which composers do you most admire / are inspired by?

I love French music – Francis Poulenc especially: I would have liked to have met him. His music is so charming, warm and witty – I often wonder if the man was like the music. Also Ravel. I love the music of Malcolm Arnold and Richard Rodney Bennett – two wonderful English composers of the 20th century whose music has had a great impact on me. Also Brahms – I love analysing Brahms – seeing the way his music unfolds is a great inspiration. And there are a great many others! I could go on and on in answer to this question!!

You’re a very busy person – how do you wind down and relax?

Hmmm… I hope I’m a fairly wound-down and relaxed sort of person as a default position! I love my work and as such spend a lot of time ‘musicking’ to use a term I rather like. Long walks and chatting with friends are always pleasures.

Can you share a top tip for students getting started with composing?

Write what you like. Don’t worry too much about rules at the start – you can assimilate those later if you want to! And remember it’s very problematic to label music good or bad. Such judgements are not very meaningful. Music just needs to be effective; to be powerful and understandable – to communicate comprehensibly beyond the capacity of words. Write what you like, write confidently and be proud of what you wish to say.

Paul Harris: Joining the Dots (March 1st, 2023)

by Phil Croydon

Paul Harris has over 600 publications to his name and shares his time among a range of activities. His published series we tend to know. But what of his other work or personal thoughts on teaching? MT's Phil Croydon meets the leading educator to fill in some gaps.

I start by asking where Harris' calling as a musician came from. He describes how, at the age of six, he acquired a grand piano in his bedroom without much explanation from his parents. They weren't musical, he says, and neither were there role models within the family. His father, a ‘hard-nosed businessman’, would probably have preferred him to follow a more worldly career. But the piano stayed and, in spite of Harris' liking for doodling rather than ‘proper practice’, he was supported. Some of his earliest compositions date from this doodling period.

His formative years as a musician came while attending Haberdashers' Boys' School in Hertfordshire. During his first concert at ‘Habs’, as a member of the school choral society, he sang Britten's Rejoice in the Lamb and Kodály's Te Deum. He enjoyed the experience so much he set his heart on a career in music. He joined the school's ‘amazing’ orchestra as soon as he could, and was soon playing Dvořák's ‘New World’.

Importance of having a good teacher

Harris is the first to acknowledge the impact teachers had on his career. He speaks fondly of the staff at Habs and in particular an exceptional clarinet teacher, John Davies, under whom he later studied at the Royal Academy of Music. Davies taught at the RAM for over 40 years, nurturing clarinettists who became international artists. But he understood how education was all ‘about drawing out, not putting in’ and building inner confidence – themes Harris would return to in his own teaching. Davies encouraged students to think broadly and encouraged him to pursue teaching as a main pathway. They became firm friends and collaborated as editors on publications such as 80 Graded Studies for wind instruments.

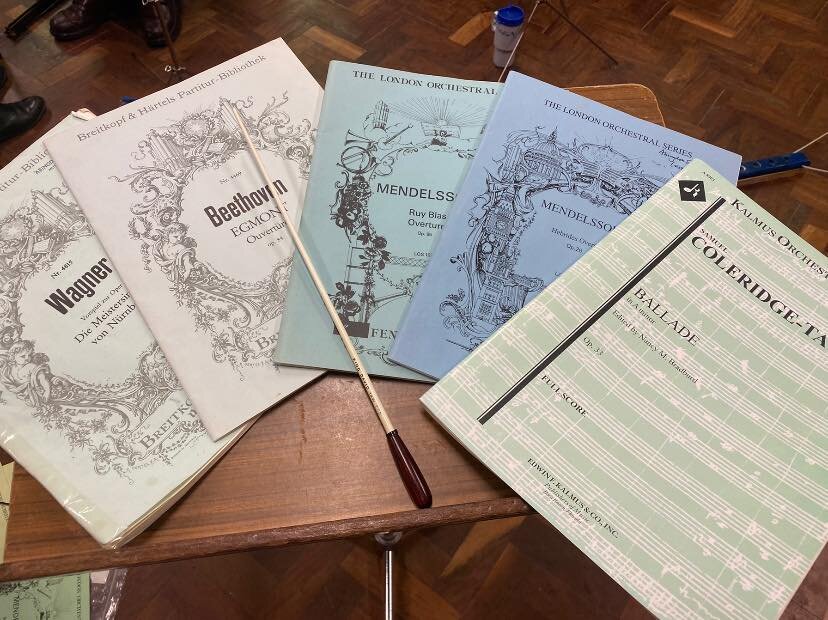

While at the RAM, Harris also studied composition and conducting. But after leaving, he attended the Institute of Education at the University of London. For a potential music educator in the late 1970s, there were few better places to be: Harris was a student of Keith Swanwick, among others, the leading researcher and thinker behind some of today's music education philosophy.

How significant was this? ‘I was lucky enough to have Keith as my tutor’, Harris says, ‘when he began writing his seminal books A Basis for Music Education and Music, Mind and Education. I found this all deeply thought-provoking.’ As with Davies, the two kept in touch.

Being a teacher

Fast forward to the 2020s and we find Harris teaching music education at the RAM, being a visiting professor at the Danish Conservatoire in Odense, offering a variety of workshops and delivering INSET courses. This scope means he has contact with a wide range of teachers. What's the advice he most often gives? ‘Be kind, be as unconditional as possible, and try to find the right route for each pupil’, he says. This positivity and empathy with players runs throughout his teaching and writing.

Our discussion moves to instrumental group-teaching in schools. Harris has followed closely the development of Wider Opportunities, First Access and similar formats. ‘Giving all children an opportunity to play a musical instrument is naturally a wonderful idea’, he suggests. ‘A good number have really benefited. But there have also been problems. Without going into great detail, I would still recommend the use of that old stalwart the recorder as a start-up instrument. It has many advantages over more sophisticated instruments; among them, being able to make a decent sound immediately, not breaking when it's dropped, and not requiring tuning. Group teaching can be very effective, but it does need thoughtful managing.’

Continuing the subject of school music, I ask what changes he'd like to see over the coming years. ‘It would be wonderful if we were able to go back to offering free tuition to those who desire to learn to play an instrument or sing’. This stems from a firm belief that music education should be available to all. He would also like to see specialist music teachers in state primary schools, where the journey for young musicians often begins.

With regards to one-to-one teaching, I'm aware that Harris has a number of private clarinet students from elementary level to post-diploma; they're taught online as well as in-person. Having researched specialist music education for highly talented players (as was the case with Julian Bliss), Harris has taken this experience with him to institutions around the globe. Are there significant differences in how to approach young virtuosos, I ask? ‘Yes. There are still some places where music teaching, especially at higher levels, is – not to mince my words – rather brutal, mostly in relation to technical work. This begs some fundamental questions such as do we need to be brutal to reach these standards?’

Educational author

Harris has published many educational titles, from collections of classical repertoire (sometimes in simplified versions) to series on sight-reading, scales and more. When asked to single out titles he's most proud of, he describes Unconditional Teaching(2021) as an important read in current times. The book received critical acclaim and was reviewed in Music Teacher (March 2022); but, essentially, it explores the environment of lessons and the pre-conditions teachers carry. It encourages teachers to identify their requirements (or ‘conditions’) early on and manage these in the interests of maintaining a two-way flow between teacher and student.

Unconditional Teaching is timely because, ‘Maybe for the first time in the history of education, we are having to fight for our survival. Being unconditional will help in a big way – we must continually move forward in a positive and productive way. So being unconditional helps us remove, or at least manage, anything that might block our journey and our pupils' journey’.

Of the other books, readers have written to the author about The Virtuoso Teacherand Simultaneous Learning, suggesting these have helped define a style of teaching, which Harris finds very satisfying. Simultaneous Learning is now a widely accepted approach, blending skills and types of activities in an imaginative and holistic way, and encouraging students to learn independently. Unconditional, The Virtuoso and Simultaneous are also in demand as a themed suite of workshops.

When looking more broadly at Harris' activities, it's tempting, I suggest, to see several symbiotic relationships. ‘Yes, definitely’, he says. ‘One of the main principles of Simultaneous Learning is that everything connects, which, if you look carefully enough, it does; so making connections between the various areas begins to become instinctive.’

For future projects, Harris is ‘working on more approaches to reading and sight-reading – if we can't read music, its future has to be in question’.

Biographer-composer-performer

In education circles, few are aware of Harris' (coauthored) biographies of Sir Malcolm Arnold, Malcolm Williamson and Sir Richard Rodney Bennett. The music of these three composers he particularly likes, but with the first, the connection runs deeper. Harris has long championed the works of Arnold (1921–2006), one of the most underrated British composers in his opinion. Arnold's fate was sealed as a ‘melody-led’ composer, Harris argues, during an era of modernist orthodoxy. This October, in Northampton, Harris will be organising the 18th annual Malcolm Arnold Festival, a festival he's proud to have founded.

As a composer of concert works, Harris is responsible for seven concertos. Five of these, the ‘Buckingham Concertos’, were written for students at Stowe School, where he worked. ‘One day’, he says, ‘I'd like to write a sixth Buckingham concerto, for violin and cello.’

As a professional clarinettist, Harris recently performed the Mozart Clarinet Quintet, the Krommer Double Concerto and is currently preparing the Malcolm Arnold concerto. In 2022, his lifelong experience of playing as well as teaching the instrument culminated in The Clarinet, a 230-page lockdown project that's a guide ‘to every facet of playing the clarinet’.

Publisher-philanthropist

In 1995 Harris established Queen's Temple Publications to make ‘interesting and useful wind chamber music’ available. QTP has since expanded to include other instruments and choral music, and has works by James Rae, Iain Hamilton, Charles Camilleri, Timothy Bowers and John Dankworth among others. It also carries the much cherished Wind Quintet Op. 2 by Sir Malcolm Arnold.

For younger musicians, Harris also runs a small Foundation. ‘I established this to help young musicians fulfill a particular ambition that will help further their musical studies and deepen their love of music.’ Every six weeks or so, awards of up to £100 are made to players in full-time education and aged between 12 and 16. He sees this as giving something back. It also speaks to his approach of being kind and unconditional.

Paul Harris interview: On no condition (March 1st, 2022)

by Claire Roberts

On the publication of his new book 'Unconditional Teaching', Claire Roberts meets Paul Harris to learn more about the concepts explored within.

Paul Harris, one of the country's leading music educationalists, has written a new book exploring the ‘conditions’ that may affect teachers and learners across all ages and instruments. Unconditional Teaching is a guide for teachers that suggests a new way forward, a new mindset, in order to create a more unconditional environment in which to live and work. ‘The book takes a look at the circumstances in which we teach, to ensure that at all times we and our pupils are in a positive frame of mind,’ says Harris.

‘It feels to me like positivity is more important than ever at a time when those of us who care about arts and culture are having to fight our corner. We can try to review the barriers, or “conditions”, that may cause negativity or frustration during lessons, in order to always have a sense of positivity about what we're doing,’ he adds.

Having written over 600 publications on various topics within music education, Harris describes this latest book as an extension of his ‘simultaneous learning’ approach: ‘Simultaneous learning is all about setting up each activity carefully so that the pupil can achieve the whole time, and a lesson is a constant series of progression. If teaching involves a pupil playing a piece, and then the teacher corrects their mistakes, a lot of students might find this negative or frustrating and feel they can't do it – or ultimately give up.’

He goes on: ‘The idea is that the simultaneous learning approach is pro-active rather than re-active. By the end of a lesson, a pupil may have carried out 20 or 30 activities, and each time has achieved something because these activities have been set up carefully. There's also a focus on “ingredients”: exploring the ingredients or features of a piece or song and making the connections between them, such as key, scale, rhythm, or technique. That's simultaneous learning in a very, very condensed nutshell!’

Developing self-awareness

Harris has previously laid out these principles in Simultaneous Learning: The Definitive Guide, which was shortlisted for the Best Print Resource Award at the 2015 Music Teacher Awards for Excellence (now Music & Drama Education Awards). Where Unconditional Teaching takes over from this, he explains, is in considering the environment of lessons – both in practical and psychological terms. In the initial chapters, Harris lists and explains some examples of conditions that could affect our teaching: the room in which we teach, the attentiveness, interest or diligence of a student, whether or not the student has remembered their books.

He also considers certain ‘hidden conditions’: unconscious bias, or beliefs we may have that are less obvious than our environment, such as giving more care or attention to students if we perceive them to possess certain musical qualities in their playing, or letting our egos influence how and what we teach. The first step in striving to teach unconditionally, according to Harris, is to acknowledge what our conditions are as teachers, so that we can try to manage or even eliminate conditions which prevent a positive mindset during lessons. But how can we go about acknowledging these conditions when they are deeply ingrained, or changing our mindset to free ourselves of certain prerequisites?

‘What we have to try to do is bring our unconscious biases into our conscious,’ says Harris. ‘Once you begin to be more self-aware, you might look back on a lesson and how you reacted in a particular moment with a student. You can delve a little deeper and think, “why did I react in that way? Is it because I believe x, y or z, and did that shape my reaction?” You then have a decision to make: you can think, I'm ok with that, or, alternatively, if I tried not to think like that, could the outcome be better?’

Harris acknowledges that it might not always be easy to become more self-aware, or to re-think our reactions, but feels that educators have highly responsible roles that demand pro-active thought and reflection: ‘I would love for all teachers to put aside five minutes at the end of a teaching day for a bit of reflection, thinking about what went well and why, and vice versa. I would love for teachers to take that responsibility – if a pupil doesn't understand something, thinking about what other pathways might lead to a different outcome, or what other connections can be made to ensure that learning is happening.’

Deeper reflection

Since he was a student himself, studying clarinet at the Royal Academy of Music, Harris has fostered a love of teaching, and has spent many years thinking and writing about music education: ‘I found it totally absorbing and fascinating. My teacher John Davies was wonderful and could tell that I really enjoyed teaching.’ Following his studies at the Academy, Harris went on to graduate with a masters in Music Education at the University of London. His teaching guides published by Faber include The Virtuoso Teacher (2012), Teaching Beginners (2008), and Improve Your Teaching!(2007), and his website includes blog posts on topics such as sight reading or practice.

This latest book, Unconditional Teaching, is testament to his own wealth of experience as a teacher. He first introduced the idea of striving to teach ‘unconditionally’ at the London Music & Drama Education Expo in 2020, after which he was encouraged to write a book on the topic. Harris explains that the notion of conditions and trying to manage them was something he had been thinking about deeply following his diagnosis of cancer in 2018: ‘I have always been healthy, so it was a real surprise to me that I was suddenly ill. I spent a lot of time thinking about how I could deal with this, and the real overriding thought I had was how could I be more unconditional, managing the conditions that were preventing me from going forward, and doing so in a positive way? We are all wired to be conditional as human beings; we can't help it, but I began to think about how this could actually get in the way – particularly for teachers.’

Unconditional Teaching is an analysis not only of the conditions or requirements that a teacher might have in their mind, but also those common to parents or learners of all ages. For example: ‘I will work harder if I can hear/see progress being made.’ Harris devised questionnaires for teachers and students of group and individual lessons and received a huge number of responses: ‘In chapter nine, I list some of the responses from students, and I was fascinated,’ he says. ‘Younger students are so incredibly aware of everything – they are aware of how they are being taught and when they are learning well, or when they aren't learning so well as a result of how something is being taught.’

Unconditional state of mind

For this reason, Harris reiterates just how important he feels it is that the unconditional teacher ‘takes responsibility’. ‘In my humble opinion,’ says Harris, ‘teaching is a hugely important job. Our younger students are the future, and, in a sense, we are shaping the future through the way in which we teach. If we create a kind of learning wherein learners don't feel frustrated or that they are not good enough, perhaps the students would feel more positive, more kind, and more responsible as they grow up.

‘In our own way, we as teachers are continually dropping little pebbles into the lake, and those ripples are then moving outwards and affecting other people. If we do our work in a compassionate and empathetic manner, we can contribute to making the world a better place in our own small way.’

The final passages of the book note the importance of being kind to oneself too. Written in the compassionate and empathetic tone that is the essence of Harris’ work as an educator, he states that teachers must take care to remember: ‘We are human. We must allow for the fact that we don't always have limitless energy and our imaginations might not always be firing on all cylinders. It's important that we accept these limitations if they occur, and not allow them to cause us stress.’ Leading by example with his kind words and positivity, Harris considers how, through increasing our awareness, we can all strive towards a state of mind that is unconditional.

Social Media

Paul Harris

Instagram feed

Queen's Temple Publications

Twitter FEED

Malcolm Arnold Festival

twitter Feed

The Unhappy Aardvark

Facebook FEED